aldous huxley who of course outlined a dystopian vision of a future world where people were centrally controlled by what he called 'world controllers' in his novel a 'brave new world'.

Quite right, dystopia is not my favourite genre, but

Brave New World is one of the better ones. It is a great examination of the operations of soft power and quite prophetic about the direction of state capitalism, with its wont to use distraction and cheap hedonism as a method of social control. I would recommend Huxley's

Island, it is in many ways a mirror image of

Brave New World; it possesses many of the same features (drug use, contraception, communities that go beyond the family unit), but is based on ideals of spiritual fulfillment, freedom and self-liberation instead of hierarchy, authority and hedonism.

George orwell on the other hand outlined a dystopian world where the state was all pervasive and ruled through fear and violence...a 'big brother state' HG Wells was also a fabian socialist and crowley pushed a credo of 'do what thou wilt' which lacks a sense of personal responsiblity

I am not much of a fan of

Nineteen Eighty-four as a dystopia—it's better as a work of Romantic tragedy. There's some real pathos in Orwell's writing and for that reason he is one of the authors who first attracted me to fiction, but like the man (who ultimately engaged in McCarthyite behaviour), the political critique is a little empty (power craves power, authoritarians rewrite history, war is self-perpetuating etc. are all quite obvious observations). I would suggest Katharine Burdekin's

Swastika Night is a better alternative; it makes many of the same points as Orwell, but did so earlier and with more insight. As for the Fabians, I don't belong to that reformist, gradualist tradition, but Wells et al. do have some good points. I think you might enjoy the nuance of

A Modern Utopia.

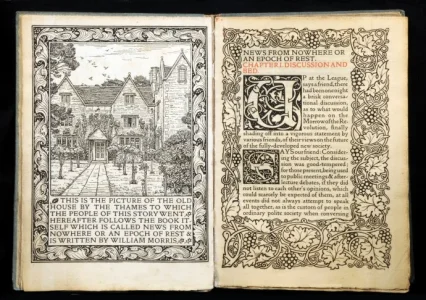

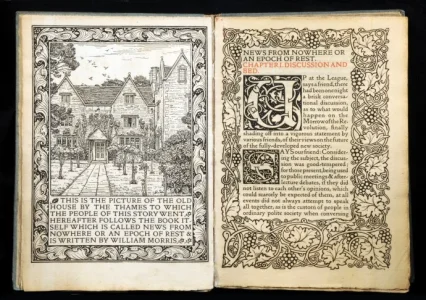

That brings us to Crowley. Now, my list is by no means an endorsement of every one of these utopian visions—it is the plurality of visions and the conversation between texts that I love about the genre. For example, William Morris's

News from Nowhere is essentially a rebuttal to Edward Bellamy's earlier utopia

Look Backward: 2000–1887. Crowley is great fun (I love learning about the traditions of esotericism, the occult, Hermeticism, alchemy and so on), but he was also an undoubtedly flawed and complex man and I doubt I would want to live in his utopia for all that I enjoy reading his strange, poetic musings.

I prefer the libertarian viewpoint of 'do whatever you want as long as it doesn't hurt others' because that contains the golden rule in it which was part of the christian ethos that crowley so despised

I am attracted to the traditions on the left that emphasise freedom and autonomy and I believe the Golden Rule is important. For me, being on the left is all about creating a society of reciprocity. I was born into Anglicanism, and although I am no longer a practicing Christian and find many of its institutions contradict my values, I am still influenced by some of its core moral tenants.

regarding the issue of an INFJ utopia i think this idea of no competition etc is too simplistic

Yes,

@Asa made the point too and it is a good one. I shouldn't be too reductive about the potential political spectrum of INFJs. I think it is better to say that there are tendencies to prefer values that might nudge INFJs towards certain ideals, tendencies that will also be shaped by other, contextual factors. I am sure there are examples of INFJs with all kinds of political beliefs, which is why I am interested to see the distinct answers I get to my question. What different utopias might INFJs write, what are the general similarities?

so for me the problem is how to reconcile a desire for maximum personal freedom that is also married to a realisation that a person owes responsibility to the people around them

A timeless question, and perhaps there will always be tensions between our freedoms and social goods. The tragedy of this tension is evoked powerfully for me by Sophocles's play

Antigone and the titular's inability to reconcile her duty to her family and her obligations to the state. How do we honour the autonomy of the person, but in a way that recognises persons as fundementally social creatures? It's a timeless question.