Yup, gonna be annoying and copy/paste everything from

this source in one giant ass post.

Top 10 Medical Advances from the Middle Ages

Top 10 Medical Advances from the Middle Ages

Medieval medicine has often been portrayed as a time when physicians were ignorant and health care remained the stuff of superstitions and quackery. However, a closer look reveals that were many ways in which medical knowledge and care improved during the Middle Ages.

1. Hospitals

By the fourth century the concept of a hospital — a place where patients could be treated by doctors with access to specialized equipment — was emerging in parts of the Roman Empire. The origins of hospitals begin in Christian religious establishments that were meant to provide lodgings and care for the poor and travellers. In Byzantium and Western Europe hospitals were usually run by monasteries and gradually became larger and more complex over the Middle Ages. Meanwhile, in the Arabic world hospitals emerged in the 8th century as more secular institutions, and in larger cities they could be staffed by dozens of physicians, had several wards for different illnesses, and could even have amenities like musicians playing in the halls.

Hôtel-Dieu de Paris circa 1500. The comparatively well patients (on the right) were separated from the very ill (on the left).

2. Pharmacies

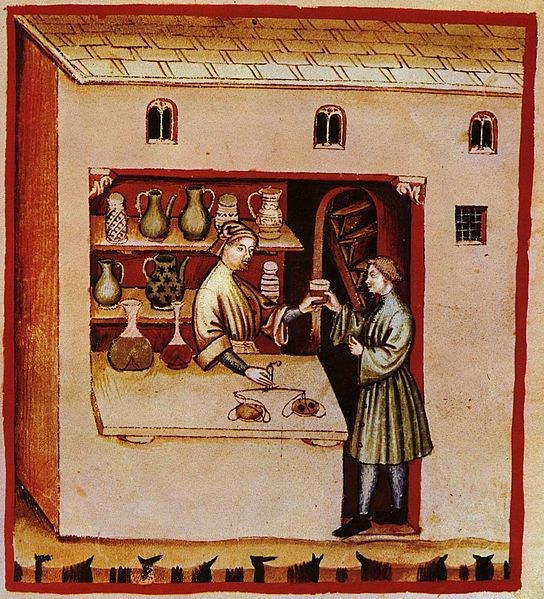

The first pharmacy was established in Baghdad in the year 754. As one medieval Arabic physician said these were places for “the art of knowing the materia medica simples in their various species, types and shapes. From these, the pharmacist prepares compounded medications as prescribed and ordered by the prescribing physician.” Pharmacies proved to be very popular and more drug stores soon opened up around the Arabic world. By the 12th century they could be found in Europe. Having pharmacies greatly aided the development of knowledge about drugs and how they could be made.

Illustration of a pharmacy in the Italian Tacuinum sanitatis, 14th century.

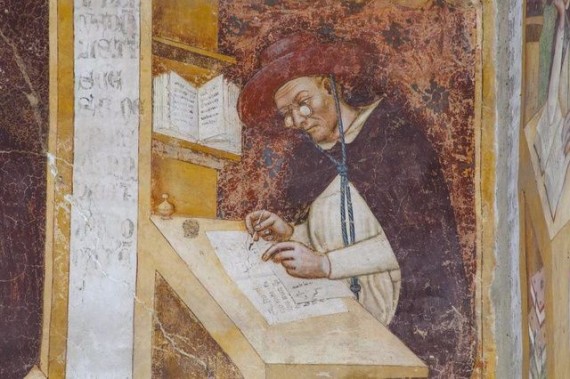

We are not sure who invented eyeglasses to help correct vision, but by the end of 13th-century it seems that the product was well known in Italy. A Dominican friar named Giordano da Pisa said in a sermon from the year 1305: “It is not yet twenty years since there was found the art of making eyeglasses, which make for good vision… And it is so short a time that this new art, never before extant, was discovered. … I saw the one who first discovered and practiced it, and I talked to him.” The earliest depiction of a person wearing glasses comes from the year 1352, when Tommaso da Modena included an image of Cardinal Hugh of Provence as part of a fresco in a church. It shows the cardinal wearing the glasses as he writes at his desk.

Tommaso da Modena depicting eyeglasses in 1352.

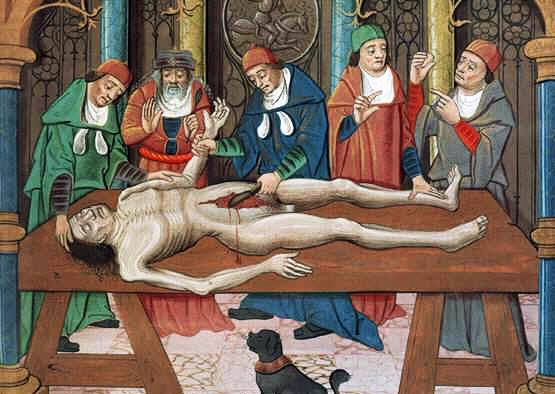

Many historians have believed that knowledge about anatomy stagnated in the Middle Ages. However, there is a great deal of evidence that medieval physicians were conducting experiments and examining the anatomy of the human body. In the year 1315 the Italian physician Mondino de Luzzi even conducted a public dissection for his students and spectators. The following year he would write Anathomia corporis humani, which is considered the first example of a modern dissection manual and the first true anatomical text.

Dissection of a cadaver, 15th century painting

The rise of universities throughout Europe would bring about important, but gradual, changes to the practices of medicine. Many medieval universities would teach physicians and become the main centres through which medical knowledge would be shared. Thomas Benedek explains in his article, ‘The Shift of Medical Education into the Universities‘: “In 1231 Frederick II promulgated a set of laws concerning medical education standards and licensure that were far ahead of his time. Although these laws did not have an immediate effect on medical training and practice, his codification of the importance of premedical education probably reinforced and stabilized an educational method which was developing and which became a cornerstone of the professionalization of physicians.”

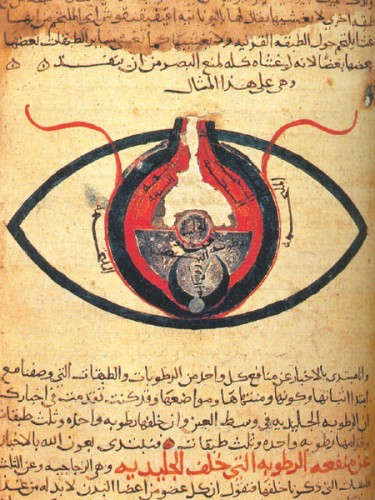

6. Ophthalmology and optics

Ancient writers believed that humans could see things through invisible beams of light that were being emanated from the eyes. The 11th century scientist Ibn al-Haytham, came up with a new explanation for vision through his research on optics and the anatomy of the eye. His work, Book of Optics, would be considered the most important research in the field for hundreds of years. Medieval Arabic physicians were also notable for their advances in the area of ophthalmology, including the invention of the first syringe, which was used to extract a cataract from the eye.

Anatomy of the Eye, from about the year 1200

Ancient medical writers believed that during surgery some pus should remain in the wounds, thinking that this would aid in its healing. This idea remained widespread until the 13th-century surgeon Theodoric Borgognoni came up with an antiseptic method, where wounds were to be cleaned and then sutured to promote healing. He even had bandages pre-soaked in wine as a form of disinfectant. The Italian surgeon is also know for pioneering the use aneasthetics in surgery. Borgognoni would make patients fall unconscious by placing a sponge soaked in opium, mandrake, hemlock and other substances under their nose.

8. Cesarean sections

While cesarean sections were practiced throughout the Middle Ages, this was done because the mother had died or had no chance of survival — and in some cases where the child was also already dead. But around the year 1500 we have the first written record of having both a mother and baby surviving a cesarean section. A Swiss farmer named Jacob Nufer performed the operation on his wife. She had been in labour for several days and was being assisted by thirteen midwives, but was still unable to deliver her baby. The operation was a success, with the mother subsequently going on to give birth to five more children, including twins. The baby lived to be 77 years old.

9. Quarantine

The concept of quarantine — to keep groups of people apart so that disease could not spread — began in the aftermath of the Black Death. In the year 1377 the city of Ragusa (now known as Dubrovnik) issued orders to combat the plague that included making arriving ships wait 30 days in the harbour before docking, so that authorities could be sure no one was infected. For land travellers this period was expanded to 40 days (in Italian quaranta). The success of these measures led to it being used in other parts of Italy and Europe by the end of the Middle Ages.

10. Dental Amalgams

One of the most important contributions to medicine from medieval China was to creation of amalgams for dental procedures. A text from the year 659 details the first use of a substance for tooth fillings, which was made up of silver and tin. The process was not used in Europe until the 16th century.