.A demonstrator at the London vigil for the victims of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Photo by Chris BethellThis article originally appeared on VICE UK.

Within hours of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, internet forums were buzzing with alternative explanations for the attack. "The official story doesn't add up," people typed furiously into their keyboards. "We're being lied to."

Over the next few days, the rumors spread. Apparent glitches in reporting–as well as the "suspicious" suicide of the detective in charge of the investigation–were taken as evidence of subterfuge.

Most doubters, however, focused on scrutinizing amateur video footage of the event, asking whether policeman Ahmed Merabet was really shot in the head.. The questioning makes for grim reading. "Where's the blood? Why no splatter?" asked Reddit users. Others offered rebuttals, posting videos of bloodless shootings and suggesting: "Heads don't explode like watermelons."

A long, imaginative list of alternative explanations was offered: It was a false flag attack, executed by Mossad to fuel anti-Muslim sentiment; it was carried out by the CIA for the same reason; it was French Jews; it was a "black-op power bloc operation" to back up the war on terror; Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that the West "playing games with the Islamic world."

Continued below.

[h=2]RECOMMENDED[/h]

[h=2]Conspiracy News: Osama Not Buried at Sea![/h]

[h=2]What Conspiracy Theories Do You Believe?[/h]

[h=2]The Man Who Tricked Chemtrails Conspiracy Theorists[/h]

[h=2]ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER MURDER CONSPIRACY[/h]

Regardless of their source, the Charlie Hebdo rumors have all the hallmarks of a classicconspiracy theory. Apparent discrepancies in the way the story was reported are jumped on, and the official version of events is discredited. From there, a leap is made to another, alternate, explanation, and evidence is gathered in support. The same thing happened after the murder of journalist James Foley, when critics suggested that the video was staged. Debunkers, in this case, asked why the West would bother faking an Islamic State beheading when the group has already carried out so many.

But how unique is the conspiracy theory-creation process? Plenty of bad journalism follows the same formula, and many an article is based on flimsy evidence and pseudoscience, or distorted by exaggerations. In the case of Charlie Hebdo, for instance, we were misled by pictures of world leaders apparently heading up the march in Paris, when really they'd just gathered in a cordoned-off street to have their photo taken.

Of course, "conspiracy theorists" is a blanket term, lumping together those who believe we're ruled by scaly lizard people with those who simply question the role of Big Pharma. Some–perhaps unsurprisingly–would like to see the name ditched altogether.

"It's a loaded term," says Chris, a friend of mine with a penchant for what most would call conspiracy theories. "It's merely a label applied to certain stories, usually to distinguish them from stories which the user of the label wishes to promote or defend by limiting the parameters of debate.

"I doubt most of what I am told, especially by those in authority, who may have an agenda to advance. The circumstances of the Charlie Hebdo attacks seem very suspicious to me, and the evidence for the official theory lacks credibility. Historical precedent also suggests that alternative narratives may be more likely."

The most recent myth to have been debunked on metabunk.org

In the US, Mick West runs the website metabunk.org, pulling in 10,000 unique visitors a day. He reckons the Charlie Hebdo rumors were predictable.

"It's nonsense," he says. "But sadly it seems like the expected response now. People pick up normal inconsistencies in the initial reporting of a chaotic situation and claim these things are significant. They always make claims about blood and injuries, but seem to be basing their expectations on the depictions of violence in movies and video games.

"It's just cherry-picking, with a strong confirmation bias. The people telling you these things have only one goal: to convince you it was fake. They amplify every little thing that seems to help their case, and they ignore everything that does not."

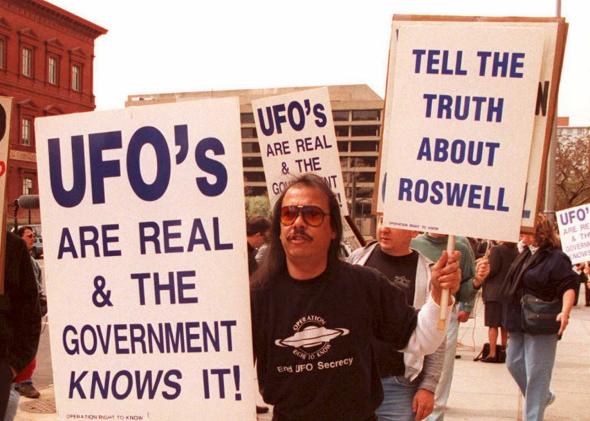

Conspiracy theories have been around for as long as human beings have been able to articulate the feeling that someone is trying to stitch them up. In living memory, theories have been espoused around the assassination of JFK, Hitler's death, the moon landings, Area 51, Princess Diana's death, the disappearance of Madeleine McCann, climate change, Obama's birth, whether Obama is in fact the Antichrist, AIDS, cancer, 9/11, chemtrails, the MMR vaccine, the Sandy Hook massacre, FEMA camps, the beheading of James Foley, Ebola, the Islamic State, the Scottish independence referendum, the Rosetta mission, and, of course, the Illuminati. And that's just a handful.

§Academics, too, have been trying to get their head around it.

"People who believe in conspiracy theories tend to feel they don't have a lot of control over their lives," says University of Winchester psychology lecturer Michael Wood. "It's reassuring to believe the world can be controlled, even if that means it's not a nice place."

Wood says that being a conspiracy theorist is just another world view, no different from being a diehard liberal or a full-on, fox-killing Tory. While right-wingers might see theCharlie Hebdo attack as evidence that uncontrolled immigration leads to problems, and those on the left suggest it's what happens when a group is marginalized, conspiracy theorists are more likely to go for the false flag explanation.

Robert Brotherton, Research Fellow at Goldsmiths, University of London, says believing in conspiracy theories fits with the way our brains make sense of the world.

"One of our psychological biases is that, whenever anything ambiguous happens, we connect the dots," Brotherton says. "The basis of many conspiracy theories is simply connecting the dots. Another is proportionality bias. When JFK got shot, people wanted to think that something big caused that, not just that some guy you'd never heard of could have killed the president."

A protester at the Anonymous Million Mask March in London, which is often attended by people espousing all sorts of conspiracy theories. Photo by Jake Lewis

But are there any factors that could signal a propensity to believe? Metrics like gender and income haven't been correlated with a belief in conspiracy theories, and there really isn't enough data available on the topic to say for certain whether–statistically–you're more likely than somebody else of a different socioeconomic group, for instance, to believe.

The advent of the internet is not thought to have swelled the ranks of conspiracy theory believers because, as quickly as the theories can be shared online, so too can their rebuttals. Some theories are plain stupid, others are less easy to dismiss.

Innate paranoia can't be a good starting point, but then not all conspiracies are a figment of the paranoid imagination. The black ops, coverups, and covert missions carried out by governments and secret services around the world are too lengthy to list in full. But to throw out a few, we've had Operation Gladio, the CIA and MI5's role in the overthrow of democratically elected governments around the world, Watergate, the Hillsborough cover-up, the Wikileaks revelations, the NSA scandal, and the discovery that, in 1990, PR firm Hill and Knowlton was behind fake testimony from a 15-year-old Kuwaiti "refugee," Nayirah, who swore she'd seen Iraqi troops killing babies.

Problem is, you can't believe every theory you hear, because many are clearly bullshit. Most of the "OPEN YOUR EYES SHEEPLE" stories you see being shared on Facebook come from sites with just as transparent an agenda as Fox News; conspiracy theories are an industry and a handful of people are doing very well out of it.

Alex Jones at the 2013 Bilderberg Conference. Photo by Matt Shea.

Alex Jones, who spews forth conspiracy theories from Infowars and other platforms, isestimated to make more than $10 million a year. Right-wing mogul Glenn Beck–who's spawned a number of bizarre theories–reportedly earned $90 million in the year from June 2012 to June 2013. Back in the UK, David Icke isn't exactly on the breadline, with an estimated $9 million net worth, much of which will have been generated through book and merchandise sales, and from tickets to the live shows where he rambles on about reptilians from the fourth Dimension ruling the world.

Plenty of conspiracy theory-espousing websites are making money through pay-per-click advertising, and you're as likely to come across a pop-up window for online gambling as herbal remedies. Make no mistake–for some, "discovering" conspiracies is a job. This isn't to say they aren't true believers, but it is in their interest to "uncover" a constant stream of conspiracies.

And all these conspiracy theories they're "uncovering" can do real harm. Antisemitic hoax document the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which claims to be a plan for global Jewish domination, has been reprinted across the globe, most notably by the Nazis in 1933. The Protocols not only served as a model for conspiracy theories–some now claim that the "Jews" depicted in Protocols are a cover identity for other groups such as the Illuminati, or, according to Icke, extra-dimensional entities–but the document's message still reverberates around conspiracy theory forums, on which Jewish groups are posited as conspiracy masterminds with depressing regularity.

In 1998, The Lancet published a study suggesting a possible link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The article was discredited and the author banned from practicing medicine. Numerous other studies have shown no such link. Nonetheless, 17 years later, many parents still subscribe to the theory that the government is trying to give their children autism in order to appease Big Pharma and, as a result, whooping cough and measles are on the rise.

Individuals have been targeted as a result of these theories. There's a movement of people who don't believe the Sandy Hook massacre really happened, suggesting it was an operation designed to revoke rights to gun ownership. Fanatics have harassed the parents of murdered children and stolen memorial signs.

A man at Occupy London 2014 who figured the best way to get his theory across was to scribble it on a sheet of cardboard in pretty much completely illegible writing. Photo by Oscar Webb

A questioning of the mainstream press seems sensible–there are direct pressures from shareholders and advertisers, there's sloppy reporting and there are agendas–but knee-jerk disbelief of anything reported by a major news source is misguided. Mainstream outlets frequently question the government and publish things those in power would rather they didn't.

Meanwhile, slavishly agreeing with everything you get from WorldTruth.tv is as sophisticated as pinning a "FUCK THE SYSTEM" badge to a branded sweatshirt made in a Bangladeshi sweatshop.

Perhaps Chris is right; the term "conspiracy theory" covers too much ground to be useful. David Cameron recently described those concerned about the alleged coverup of a VIP pedophile ring as "conspiracy theorists." His intention: to instantly discredit them.

But danger lies in using the small amount of energy you have for politics on chasing illusions. There are plenty of real problems to confront. Question mainstream news, sure, but don't fall into the trap of believing everything you read on Infowars and its ilk. Everyone has an agenda.

Follow Frankie on Twitter

[Images] The Psychology of Conspiracy Theorists and Theories

- Thread starter Stu

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

.[h=1]The Man Who Tricked Chemtrails Conspiracy Theorists[/h]October 13, 2014

by Michael Allen

[*=center] Share

[*=center] Tweet

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

Some airplane condensation trails, which conspiracy theorists believe are "chemtrails." Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The chemtrails conspiracy theory has been circulating for a while among the same sorts of people who believe that 9/11 was an inside job and celebrities are being controlled by the CIA. In brief, chemtrail enthusiasts think that those white trails of vapor you see pouring out of planes are actually nasty chemical or biological agents that governments are using to geo-engineer the weather, create a vast electromagnetic super-weapon, control the population, or—well, you get the idea. There's no science or proof whatsoever behind this, but plenty of people are still willing to entertain this vaguely supervillain-esque notion.

Chris Bovey in Argentina

On October 1, Chris Bovey—a 41-year-old from Devon, England—thought he’d troll the chemtrails camp. During a flight from Buenos Aires to the UK, his plane had to make an emergency landing in São Paulo and dumped excess fuel to lighten the load. Since he had a window seat, Chris decided to film all the liquid being sprayed out of the wing next to him.

Continued below.

[h=2]RECOMMENDED[/h]

[h=2]Conspiracy Theorists Are Dangerous Enemies to Make[/h]

[h=2]The Conspiracy Theory About Obama Hoarding Ammo Is Causing Real Trouble[/h]

[h=2]Uncovering the "Truth" Among the Conspiracy Theorists at the 2013 Bilderberg Fringe Festival[/h]

[h=2]What’s Behind All the Right-Wing Cop Shootings?[/h]

Touching down, he uploaded the video with a caption that suggested it could be evidence of chemtrails, hoping to mess with a couple of friends who he knew might fall for it. The video now has 1.1 million views, nearly 20,000 shares, and dozens of comments telling viewers to “wake the F up," or accusing naysayers of being “stupid paid shills."He then claimed (falsely) that he’d been detained at Heathrow upon arrival, been interrogated by the authorities, and had his phone confiscated. That riled everyone up even more, with “conspiraloon” (Chris’s term) website NeonNettle.com picking up the story and reporting it as evidence of chemtrails.

The video Chris filmed from his seat

Mick West—editor of anti-conspiracy theory website Metabunk, which published an article explaining why Chris’s video was a hoax—explained the history of the chemtrails theory to me. “It started back in the late 1990s,” he said. “People just noticed contrails—the condensation trails behind planes—for the first time, and got this idea that a normal contrail shouldn’t persist for very long. So if anything lasted for more than a few minutes, itmust be something being sprayed.”

While chemtrails advocates might accuse sheeple of believing everything their governments tell them, they themselves tend to believe a lot of the stuff their internet tells them. West thinks its the proliferation of unverified “evidence” online that’s led to this particular conspiracy theory remaining so popular.

“People share things that look interesting without really looking into them, and they take the word of whoever’s posting it that it’s a real thing,” he said. “I knew from the start that it was some kind of hoax, but people want to have their worldview confirmed, so when they see something that seems to fit their worldview they jump on it.”

In Chris’s case, that involved being invited onto a radio show hosted by Richie Allen, a friend of David Icke—the man who claims we’re being ruled by a group of lizard overlords disguised as world leaders. On air, Chris admitted that the whole thing was a hoax and got into an argument with the host about the validity of the chemtrails theory.

Since then, Chris has been subject to a stream of “vulgar abuse” from pissed-off conspiracy theorists—which, admittedly, is completely his own fault. I gave him a call to find out how he was doing.

VICE: So I hear you’ve been receiving some pretty bad abuse since you duped these conspiracy theorists?

Chris Bovey: Yeah, I got some really foul messages. I got accused of being a government paid shill—so where’s my paycheck? The worst bit of abuse is on my Facebook page. I left it up there because it’s so insulting that it made the guy look like an idiot. It was about goat fucking and how I was going to get butt-fucked in prison.

Someone else said I was going to hell for breaking the First Commandment. I’m not religious; I don’t know what the First Commandment is. Maybe it’s, “Thou shalt not post fake chemtrail hoaxes.” [Note: it is actually, "Thou shalt have no other gods before me."] Other people were saying I’d been leaned on to change my story, saying that it was really a chemtrail-molecule dump.

Why do you think people were so quick to believe your video was evidence of chemtrails?

I think people want to believe it, and I think people are so distrusting of the government. It says a lot about our government that people are actually prepared to believe that they would do this. It’s a lack of basic scientific understanding. It doesn’t take much research—if you go onto contrailscience.com, you can quite easily see it explains why they’re formed.

A video claiming that easyJet wouldn't be able to sustain itself were it not being paid off to dump chemicals during flights.

Have people stopped claiming that the video is evidence of chemtrails now that you’ve come out and explained it?

Not at all. There are still people sharing it as we speak, saying “chemtrails” in all sorts of languages—some I don’t even recognize.

I’ve got a good 500 people who sent me friend requests, and I accepted them, but today I deleted them all because they kept on inviting me to "like" various strange pages. I knew these kinds of people existed—that’s why I posted it. But I absolutely didn’t realize how strongly these people believed this. With a few of them, I’ve tried to reason with them by sending evidence to explain why they are wrong, and they generally just called me a shill and blocked me.

How long have you been interested in chemtrails?

I remember seeing them as a little child when I was at primary school on the River Dart, where I grew up in South Devon. On the playground I used to look up in the air and notice that some planes had longer trails and wonder why. Of course, at that point I didn’t realize it was an Illuminati plot.

Why did you admit the video was a hoax and not keep it going?

At the time, I was getting a little bit uncomfortable with it, partly because I didn’t want my sane friends thinking I was an idiot. So it was an ideal opportunity to come clean and also a great opportunity to prank them.

Do you think there’s any evidence to support the chemtrail theory at all?

No, it’s just completely debunked. There’s zero evidence—zilch.

Follow Michael Allen on Twitter.

.[h=1]Man Claimed He Was Detained At Heathrow For Filming Chemtrails Hoax[/h]By: Sasha Sutton |@SashaEricaS

[h=2]Chris Bovey Admitted Hoax On Richie Allen Show[/h]

on 2nd October 2014 @ 5.45pm

Tweet

© Chris Bovey/Facebook

The police were very threatening and kept me hanging around for ages, asked stupid questions and took my phoneA man who filmed an alleged chemtrail spraying from the wing of a plane whilst he was a passenger, had claimed he was detained by police at Heathrow after the video went viral. The Video has now set the conspiracyworld alightChris Bovey captured the footage during a commercial flight, as he posted on his facebook page that he had security pounce on him as soon as he touched down in Heathrow – detaining him for eight hours - which turned out to be false.“Finally got home to Devon. Detained by security at Heathrow. iPhone confiscated. I tried to explain I uploaded it from the plane after it landed and that the video was already online, but they wouldn't listen. eight hours in a holding cell. FML”, said Bovey in a Facebook post.The officers also confiscated Bovey’s phone in a bid to seize the content, which he had used to record the shocking event on the plane.“The police were very threatening and kept me hanging around for ages, asked stupid questions and took my phone, it was a f**king expensive phone it had all my contacts in it"“I'm quite angry about it, I'm going to call a lawyer”.© Chris Bovey/Facebook

The Video has now set the conspiracy world alight

This is not the first time someone has been arrested for potentially exposing the chemtrails cover-up. UFO Sightings Hotspot reported that at the beginning of this year, EUCAH public information director Melanie Vristchan was unlawfully arrested in Brussels and placed in a mental institution after proposing a ban on HAARP and chemtrails, under EU law.He said on Facebook - “They took my bags and shoved me, handcuffed, inside the police car”, she said in a statement published by Exopolitics.“They then took me to a room where the female officer searched my body and they waited with me until a psychiatrist arrived at which time they left the room. The psychiatrist told me that he had received the order from the Prosecutor to have a psychiatric admission exam with me”.Lucky for Bovey, he was not sent to a psychiatric hospital and was eventually released by officers. But since his video has been shared over 10,000 times on Facebook, it seems he may have found fame as this footage could expose something big, however, it the claims have turned out to be falseMetabunk have since issued this statement: "On Tuesday September 30th, 2014, flight BA244 from Buenos Aires, Argentina to London, UK, was diverted to Sao Paulo shortly after departure, due to an unusual odor in the cabin. As the 777 was fully loaded with fuel for the long flight, it was unable to immediately land, as it was over-weight. So the plane had to dump fuel until it reached a safe landing weight.Read the full Metabunk post here. Photo Credit: Chris Bovey/Facebook

tags: chemtrails| Conspiracy

...[h=1]Uncovering the "Truth" Among the Conspiracy Theorists at the 2013 Bilderberg Fringe Festival[/h]June 12, 2013

by Matt Shea

[*=center] Share

[*=center] Tweet

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

[*=center]

Every year, the Bilderberg Group—a collection of some of the world's most powerful people—gets together to discuss how to keep on being powerful. Now, considering that the past couple weeks haven't been great ones for democracy (shouts to Turkey and theNSA!), I don't blame you if the prospect of powerful government officials holding a closed-door meeting with the financial elite gets your goat a little. Especially since while the big swinging dicks gathered in Watford, England, last weekend, unemployment in the UK continued to rise, cities in Turkey kept on burning, and the war in Syria remained the stuff of nightmares.

While you might look at these worldwide messes and see a lot of basic human weakness and error, conspiracy theorists read the news, see the word Bilderberg, and immediately start connecting the dots: the puppet masters are poisoning the water supply, they're enslaving your mind—bad events aren't the result of human weakness or error at all, but a malicious plan being orchestrated against humans by a New World Order of aliens from space. You can argue that with a guestlist that includes David Cameron, IMF chief Christine Lagarde (one of 14 women among 134 delegates), David Petraeus, and the heads of BP, Goldman Sachs and Shell, the Bilderberg Group should make its high-level discussions open to the public. Unfortunately, the legitimate demand for allowing media inside the conference gets discredited by the swarms of conspiracy theorists who show up at the event each year to stand outside the gate and scream stuff about secret occult societies.

Sure enough, when the Bilderbergers arrived at the five-star Grove hotel in Watford, they were joined by the biggest crowd of conspiracists to date. In fact, the protesters had decided to create an official event and so the inaugural Bilderberg Fringe Festival was born, complete with a campsite, makeshift press tent, security, and the biggest names in the conspiracy world, including David Icke and Alex Jones. So what's the latest in secret truths dreamt up by the powerful to fuck us? I went down to the Grove to test the (fluoride-saturated) waters.

When I arrived, the police had put a one-in, one-out policy in place. "The event has already exceeded capacity," they shouted. "We intended to have 1,000 people there; there are now 2,000. Please keep off the grass."

"Keep off the grass? Is that what we're paying our taxes for?" one guy shouted, to whoops and cheers from the crowd. I waited patiently for my turn to get closer to the fringe festival, along with a bunch of totally legit media organisations, like InfoWars, WeAreChange, and Truthjuice. Everyone seemed nervous and the air smelled of Cannabis Cup-winning weed. I wondered whether these two phenomena might be connected in some way.

Indie Meds, who "put the pieces together" himself.

After watching journalists who figured it wasn't worth the wait to get inside peel off all around me, I finally got through. Alex Jones, the keynote speaker, hadn't begun his speech yet, so I started making friends.

"What’s your name?" I asked a guy in a brown robe.

"Indie Meds. That’s my enlightened name since I started to wake up."

"When did you wake up?"

"I started to wake up about a year ago, when I had a stroke on the left side of my brain. Afterwards, my aware side woke up and I started to notice that the news was a load of rubbish. I started doing my own research into Egyptian pyramids, the Mayans, sacred geometry, the whole package—and aliens. They all sort of came together in a package and I put the pieces together myself."

"What ties all those things together?"

"The message is the same—back to the Mayans, back to the Egyptians and back to the Atlantians even before that: you are God; you are one."

At the back of this photo, past the security, is the Grove, where the Bilderberg Group was meeting.

"What does this have to do with Bilderberg?"

"Bilderberg’s just part of the power game," Indie Meds told me. "All the wars, all the media, all the politics, all the religions. I’m sure they’re tied in with the Vatican, too. Once you start doing research, you find you can link everything together, and once you’ve linked it together it changes your outlook on life."

"OK. What’s the costume for?"

"Because I like dressing up as a Jedi."

After speaking to Indie Meds, I was still confused. What did it mean to be "awake"? Do I need to have a stroke in order to wake up? And how did sacred geometry have anything to do with a load of powerful people who meet once a year without any cameras present? I asked some more people for help.

Philis (left) and Jud Charlton.

Maybe Jud Charlton and his ventriloquist dummy, Philis, could help me wake up.

“The idea with Ventriloquism Against Conspiracy (VAC) is that we come together," Jud said.

"If I came on my own, it’d be no good," chuckled Phillis.

"Fair enough," I replied. "What's the conspiracy?"

“It's all about: let’s get the information out. Let’s get all the stuff that they’re doing out.”

Many of the "awake" people seemed to spend a lot of time sleeping.

"What are they doing?"

“Well, that’s the issue, isn’t it?"

I stared blankly at him for a few seconds. "Yes. Wait—what's the issue again?"

Before I could ask any more questions, a wave of hollers and people shouting the Star Wars "Imperial March" song told me that Alex Jones had taken to the podium. The main event was about to begin.

Alex Jones before his admiring audience.

I'm sure you know who Alex Jones is. If you're not, he can best be explained as kind of like a WWE wrestler who adopts the persona of an extremely paranoid person every time he enters the ring. He seems to have mastered the debating technique of overwhelming you with such a torrent of falsehoods that you couldn't possibly address them all in real time.

"If you think hundreds of raped children and necrophilia is anything, that again is only the surface," he began, gently feeling his way into the swing of things.

There was a lot of weird electrode shit going on.

"They might kill me for getting up here and telling you this, but they have been putting out cancer viruses—that’s why there are hundreds of new bizarre cancers that never existed," Jones continued. "That’s why, 30 years ago—I've talked to medical doctors—doctors would fly across the country to see a child with cancer. Now I can walk out my front door and see children with cancer playing in the playground any time I go there, with their chemotherapy roach poison injectors hooked up to them!"

The crowd cheered.

"These cops. Every one of these cops. Within six years, 40 percent of them will have cancer."

The crowd laughed and cheered. Haha! Cancer.

A little girl breaks through the security line, presumably to join the Illuminati.

"Seriously. By 2030, it'll be more like 70 percent, so these cops will remember when they're burying their young child of cancer and they'll say, 'Oh, this cancer never existed 20 years ago, but all the kids are getting it. Now, let's not discuss why it’s happening, let’s discuss donating money to find the cure.' It's like if Jack the Ripper was stabbing people and we looked for a way to heal them instead of finding Jack the Ripper!"

In case you didn't understand that, which is excusable because it makes literally no sense, what Jones is essentially advocating is, "Instead of giving money to cancer research to find out where new cancers come from and how to treat them, let's stop that and start accusing businessmen and politicians of inventing new, impossibly secretive ways to mutate our genes." It's unclear what exactly the Bilderbergers are getting out of giving everyone cancer.

He then led the crowd in a chant of, “We know you are killers!” Presumably this was aimed towards the Grove Hotel, a good 650 yards away.

:

...

Towards the end of the speech, a lone provocateur jumped up and began accusing Jones of being part of the New World Order himself, infuriating the loyal crowd, who yelled, “Police! Arrest him!” The level of irony in the air was suffocating me. I couldn't help but imagine the provocateur preaching to his own devoted legion of bedraggled conspiracy theorists: The Bilderberg Fringe Festival Fringe Festival.

At the BFFFF, you can be sure there will be yet another provocateur who will interrupt the first one’s speech with passionate cries for the truth (the real truth). Hundreds of years from now, when everything is exposed to history, it will come to surface that that guy—the conspiracy theorist who dared to doubt the conspiracy theorists who in turn doubted the mainstream conspiracy theorists like Jones, who dared to doubt the Bilderberg New World Order—was right.

Trevor, a.k.a. Noisy Parrot.

Despite being buried beneath an avalanche of new information, I still didn't really come away from Jones's speech with any proper understanding of what was going on. So I asked some people if they could dumb it down for me.

"What do you think the main point of Alex’s speech was?" I asked Trevor, who goes by the name Noisy Parrot.

"Trying to enlighten us to what’s going on behind the scenes."

"What is going on behind the scenes?"

"Well, it’s the Bilderberg meeting."

I sighed. "Why do you have elf ears on?"

"Oh, they’re actually fairy ears. I roll with a group of fairies."

Janet (left) and Valerie.

I turned to two of those fairies, Janet and Valerie, to ask, "What do you guys think the main point of Alex’s speech was?"

"Just to spread awareness, I think," said Janet. "To see so many like-minded people come together, it makes me think that there is a shift happening."

"Yeah," Valerie agreed.

"A shift in what?" I asked. "Please can you explain to me what I'm supposed to be aware of?"

"So many people I know are finding things so incredibly different in the past few years. I think people are starting to wake up," said Janet, before prancing away with Valerie. I'm guessing they were off in search of better vibes and people who weren't asking them questions about why they were asking questions.

But I had every right to be frustrated. I'd come here to figure out what was going on inside Bilderberg—or, at least, what these people thought was going on inside Bilderberg—and no one could give me a straight answer. It was around this time that I began to notice a worrying number of children playing around the "spiritual healing zone" that had apparently been set up to counteract whatever dark ceremonies were going on at Bilderberg. I couldn't help but wonder how many of these kids were being ushered into a life of paranoia and strange looks every time they tried to strike up conversations about what "really matters" during history classes.

But maybe I was just being cynical. Maybe they regularly contribute much-lauded op-eds to InfoWars and were here of their own accord? Maybe, with their naive, uncomplicated take on the event, they could help me to finally wake up?

I asked a little girl what she thought about the Bilderberg Conference.

"Ummm. Very fun!" she said, to my surprise. Very fun? Did she have a part to play in the New World Order, too? Was this all some kind of game to her?

"What do you think is going on over in that hotel?" I probed.

"I’m not sure," she said. I wasn't convinced.

"Is it where the New World Order meets to discuss eugenics programs?"

"Yeah!"

I got out of there as fast as I could before she injected cancer into my blood.

This lady's shirt reads, "I went to Bilderberg 2013 and all I got was this lousy New World Order."

By now, I'd met lots of very opinionated people who didn't seem to want to disclose any opinions other than the fact that the Bilderbergers were the guys behind cancer. But I didn't quite feel awake yet. Now, I've been to enough of these type of events to know that you can always find hot girls at the hula hoop circle, and I thought that maybe the hot girls could help wake me up.

Francesca.

Francesca had a killer smile. If auras are real, she definitely had one, and I could totally feel its energy. I think she could feel mine, too.

"What brings you here today?" I asked.

"I’ve come here to spread as much unconditional love as I can. To everyone. And I think it’s working—I can feel it."

"Me too, I think it’s working. What do you think was the main point of Alex’s speech?"

Fringe Festival security guards escort someone away.

"They’re just making people aware, which is great. I love the fact that they’re here doing the right thing and speaking the truth."

"What are they making people aware of, specifically?"

"Of what exactly is going on in the world. We’re not listening to the media and all that. This is actual, y'know, important stuff."

I was a little upset that Francesca didn't have any answers for me, either, until she told me that she loved me and hugged me goodbye.

Bryony.

"What brings you here today?" I asked a girl named Bryony.

"People, everyone, connecting and information," she replied.

"What information, specifically?"

"Uh, about the… people in there. What are they called?"

"Bilderberg?"

"The Bilderberg, yes. We shall not surrender to these people who are trying to control us and oppress us. And poison us."

"How are they poisoning us?"

"They’re poisoning us by putting fluoride in the water and genetically modifying nature."

"So does everyone in there support water fluoridation?"

"Like, here’s the thing—I came here with an open mind. I know there are people in there who are trying to do the right thing. I came here to connect with people and to love."

I had expected conspiracy theorists to jump me from every angle while they tried to explain the "truth," but the people at the Bilderberg Fringe Festival I spoke to got flustered and couldn't really tell me what they believed, at least not in a way that I could understand. The only thing everyone seemed to agree on was that Bilderberg is somehow controlling/killing us through water fluoridation. I can't help but thnk that if that was the case, they wouldn't really need to meet for more than five minutes to discuss how to do that. ("Let's put some more fluoride in the water supply!")

It's no wonder that in times of economic hardship people want someone to blame, but if the hippies and shock jocks at the BFF can't channel their anger into something useful, it discredits everyone else who's genuinely fighting for change. We all know that when you take drugs everything seems connected in some giant cosmic conspiracy, but the solutions to the world's problems aren't as simple as trying to expose a secret cabal of lizard people intent on ruling the world. Solving the world's problems takes a lot more hard work and dedication than that, and less scapegoating of non-existent entities.

Follow Matt on Twitter: @Matt_A_Shea

More on conspiracy theorists

https://clonefive.wordpress.com/2013/07/23/the-anatomy-of-a-conspiracy-theorist/THE ANATOMY OF A CONSPIRACY THEORIST

July 23, 2013 · by clonefive · Bookmark the permalink. ·

Image courtesy of berkley.edu.

What is a conspiracy theorist? A conspiracy theorist is defined as one who follows a theory seeking to explain a disputed case or matter as a plot by a secret group or alliance rather than an individual or isolated act that possesses little to no factual foundation. I present five common traits that conspiracy theorists appear to universally share between each other.

Many conspiracy theorists share the inability to accept information that differs from the conspiracy theorist’s perspective, regardless of the credibility differential between the two sources of information regarding the cause. This is an example of a logical fallacy, in which an argument is rendered invalid due to it being inherently one-sided and closed off to criticism – via this concept, conspiracy theorists do not truly possess an ”argument”, but a one-sided conjecture that only acts as a cascade catalyst for other conspiracy theorists.

Conspiracy theorists frequently present ”red herrings” towards individuals of the opposing mindset – the frequent, presumably impulse-driven arisement of irrelevant arguments that detract from the original argument and invoke irrelevant conversation in effort to avoid confrontation against the conspiracy theorist’s original cause. Additionally, such theorists present the viewpoint that if such sources are scientific and detract the cause that the conspiracy theorist possesses, then such sources must be ”fabricated”, despite the conspiracy theorist linking ”sources” that consist of YouTube videos and information sheets with no citations or references.

Another aspect that is common is that of a profound sense of ”superiority” over the sceptic, and that they are ”right” and hold more credibility than anybody else and ask why others cannot ”see” whatever patterns the conspiracy theorist is observing that cannot typically be observed by the majority of individuals and only those who meticulously seek out or fabricate patterns and attempt to decipher them into a fantastical explanation and resorting to personal confrontation to those who do not share the same viewpoint(s), disregarding the logical philosophy of Occam’s Razor method of critical thinking – ”I see a shape in the water, therefore it must be a mythological creature as written about in folklore!” and disregarding more logical explanations for the more fantastical one, so as to correspond to one’s own personal basis regardless of evidence or logic much to the contrary.

Such traits are somewhat similar to those presented in patients with paranoid schizophrenia, in which meaningless events are viewed by one’s internal mind to be significant in value, regardless of opinion or evidence that refutes such a significance. It is important to acknowledge that speculation and conjecture does not constitute as fact, regardless of personal beliefs or suspicions.

In conclusion, conspiracy theorists present many logical fallacies and flaws in critical reasoning – many of which are essential in the understanding of concepts behind conspiracy theories in themselves. Unfortunately, this method of reasoning provokes ”herd” mentality, and others join in on conspiracies, despite the lack of evidence in favour of their cause, and evidence presented against their cause.

Bibliography

Article written by Miles B. Please credit both the author’s and the domain’s name in references.

Last edited:

Ok lets do this....

The term 'conspiracy theorist' was created by the CIA and planted into the mainstream media (they infiltrated it through operation mockinbird: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Mockingbird ) to be used against anyone who questioned the 'magic bullet' theory of the warren commission when it published its fidnings of its investigation into the assassination of John F Kennedy in which they said a single bullet caused massive damage within the car to the vehicle and to two people

They then said that the following undamaged bullet was the one they found in the body of the president at the hospital:

Does that look like a bullet thats wreaked a lot of damage?

The commission said that Oswald acted alone and got off 3 shots in 6 seconds leaving no traces of powder on his cheek; oswald himself said he was a 'patsy'

So anyone who questioned these discrepancies and many others was then labelled a 'conspiracy theorist'

Lets look some more into this...

The term 'conspiracy theorist' was created by the CIA and planted into the mainstream media (they infiltrated it through operation mockinbird: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Mockingbird ) to be used against anyone who questioned the 'magic bullet' theory of the warren commission when it published its fidnings of its investigation into the assassination of John F Kennedy in which they said a single bullet caused massive damage within the car to the vehicle and to two people

They then said that the following undamaged bullet was the one they found in the body of the president at the hospital:

Does that look like a bullet thats wreaked a lot of damage?

The commission said that Oswald acted alone and got off 3 shots in 6 seconds leaving no traces of powder on his cheek; oswald himself said he was a 'patsy'

So anyone who questioned these discrepancies and many others was then labelled a 'conspiracy theorist'

Lets look some more into this...

http://www.usnews.com/science/articles/2009/05/26/the-inner-worlds-of-conspiracy-believers

By Bruce Bower, Science News

Shortly after terrorist attacks destroyed the World Trade Center and mangled the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, conspiracy theories blossomed about secret and malevolent government plots behind the tragic events. A report scheduled to appear in an upcoming Applied Cognitive Psychologyoffers a preliminary psychological profile of people who believe in 9/11 conspiracies.

A team led by psychologist Viren Swami of the University of Westminster in London identified several traits associated with subscribing to 9/11 conspiracies, at least among British citizens. These characteristics consist of backing one or more conspiracy theories unrelated to 9/11, frequently talking about 9/11 conspiracy beliefs with likeminded friends and others, taking a cynical stance toward politics, mistrusting authority, endorsing democratic practices, feeling generally suspicious toward others and displaying an inquisitive, imaginative outlook.

“Often, the proof offered as evidence for a conspiracy is not specific to one incident or issue, but is used to justify a general pattern of conspiracy ideas,” Swami says.

His conclusion echoes a 1994 proposal by sociologist Ted Goertzel of Rutgers–Camden in New Jersey. After conducting random telephone interviews of 347 New Jersey residents, Goertzel proposed that each of a person’s convictions about secret plots serves as evidence for other conspiracy beliefs, bypassing any need for confirming evidence.

A belief that the government is covering up its involvement in the 9/11 attacks thus feeds the idea that the government is also hiding evidence of extraterrestrial contacts or that John F. Kennedy was not killed by a lone gunman.

Goertzel says the new study provides an intriguing but partial look at the inner workings of conspiracy thinking. Such convictions critically depend on what he calls “selective skepticism.” Conspiracy believers are highly doubtful about information from the government or other sources they consider suspect. But, without criticism, believers accept any source that supports their preconceived views, he says.

“Arguments advanced by conspiracy theorists tell you more about the believer than about the event,” Goertzel says.

Swami’s finding that 9/11 conspiracy believers frequently spoke with likeminded individuals supports the notion that “conspiracy thinkers constitute a community of believers,” remarks historian Robert Goldberg of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Goldberg has studied various conspiracy theories in the United States.

Conspiracy thinkers share an optimistic conviction that they can find “the truth,” spread it to the masses and foster social change, Goldberg asserts.

Over the past 50 years, researchers and observers of social dynamics have traced beliefs in conspiracy theories to feelings of powerlessness, attempts to bolster self-esteem and diminished faith in government. Some conspiracy beliefs — such as the widespread conviction among blacks that the U.S. government concocted HIV/AIDS as a genocidal plot — gain strength from actual events, such as the once-secret Tuskegee experiments in which black men with syphilis were denied treatment.

Swami and his colleagues administered a battery of questionnaires to 257 British adults, including a condensed version of a standard personality test. Participants came from a variety of ethnic, religious and social backgrounds representative of the British population.

Most participants expressed either no support or weak support for 16 conspiracy beliefs about 9/11. These beliefs included: “The World Trade Center towers were brought down by a controlled demolition” and, “Individuals within the U.S. government knew of the impending attacks and purposely failed to act on that knowledge.”

Much as Swami’s team suspected, beliefs in 9/11 conspiracy theories were stronger among individuals whose personalities combined suspicion and antagonism toward others with intellectual curiosity and an active imagination.

A related, unpublished survey of more than 1,000 British adults found that 9/11 conspiracy believers not only often subscribed to a variety of well-known conspiracy theories, but also frequently agreed with an invented conspiracy. Christopher French of Goldsmiths, University of London, and Patrick Leman of Royal Holloway, University of London, both psychologists, asked volunteers about eight common conspiracy theories and one that researchers made up: “The government is using mobile phone technology to track everyone all the time.”

The study, still unpublished, shows that conspiracy believers displayed a greater propensity than nonbelievers to jump to conclusions based on limited evidence.“It seems likely that conspiratorial beliefs serve a similar psychological function to superstitious, paranormal and, more controversially, religious beliefs, as they help some people to gain a sense of control over an unpredictable world,” French says.

Swami now plans to investigate attitudes of British volunteers to conspiracy theories about the July 7, 2005, terrorist bombings in London.

http://www.slate.com/articles/healt...claim_to_know_the_truth_about_jfk.single.html[h=1]Conspiracy Theorists Aren’t Really Skeptics[/h]15.9k356

529

[h=2]The fascinating psychology of people who know the real truth about JFK, UFOs, and 9/11.[/h]By William Saletan

Believing in conspiracy theories doesn't make you any less gullible than people who buy the "official story."

Photo by Joshua Roberts/AFP/Getty Images

To believe that the U.S. government planned or deliberately allowed the 9/11 attacks, you’d have to posit that President Bush intentionally sacrificed 3,000 Americans. To believe that explosives, not planes, brought down the buildings, you’d have to imagine an operation large enough to plant the devices without anyone getting caught. To insist that the truth remains hidden, you’d have to assume that everyone who has reviewed the attacks and the events leading up to them—the CIA, the Justice Department, the Federal Aviation Administration, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, scientific organizations, peer-reviewed journals, news organizations, the airlines, and local law enforcement agencies in three states—was incompetent, deceived, or part of the cover-up.

WILLIAM SALETANWill Saletan writes about politics, science, technology, and other stuff for Slate. He’s the author of Bearing Right.

And yet, as Slate’s Jeremy Stahl points out, millions of Americans hold these beliefs. In a Zogby poll taken six years ago, only 64 percent of U.S. adults agreed that the attacks “caught US intelligence and military forces off guard.” More than 30 percent chose a different conclusion: that “certain elements in the US government knew the attacks were coming but consciously let them proceed for various political, military, and economic motives,” or that these government elements “actively planned or assisted some aspects of the attacks.”

How can this be? How can so many people, in the name of skepticism, promote so many absurdities?

ADVERTISING

The answer is that people who suspect conspiracies aren’t really skeptics. Like the rest of us, they’re selective doubters. They favor a worldview, which they uncritically defend. But their worldview isn’t about God, values, freedom, or equality. It’s about the omnipotence of elites.

Conspiracy chatter was once dismissed as mental illness. But the prevalence of such belief, documented in surveys, has forced scholars to take it more seriously. Conspiracy theory psychology is becoming an empirical field with a broader mission: to understand why so many people embrace this way of interpreting history. As you’d expect, distrust turns out to be an important factor. But it’s not the kind of distrust that cultivates critical thinking.

In 1999 a research team headed by Marina Abalakina-Paap, a psychologist at New Mexico State University, published a study of U.S. college students. The students were asked whether they agreed with statements such as “Underground movements threaten the stability of American society” and “People who see conspiracies behind everything are simply imagining things.” The strongest predictor of general belief in conspiracies, the authors found, was “lack of trust.”

But the survey instrument that was used in the experiment to measure “trust” was more social than intellectual. It asked the students, in various ways, whether they believed that most human beings treat others generously, fairly, and sincerely. It measured faith in people, not in propositions. “People low in trust of others are likely to believe that others are colluding against them,” the authors proposed. This sort of distrust, in other words, favors a certain kind of belief. It makes you more susceptible, not less, to claims of conspiracy.

Once you buy into the first conspiracy theory, the next one seems that much more plausible.

A decade later, a study of British adults yielded similar results. Viren Swami of the University of Westminster, working with two colleagues, found that beliefs in a 9/11 conspiracy were associated with “political cynicism.” He and his collaborators concluded that “conspiracist ideas are predicted by an alienation from mainstream politics and a questioning of received truths.” But the cynicism scale used in the experiment, drawn from a 1975 survey instrument, featured propositions such as “Most politicians are really willing to be truthful to the voters,” and “Almost all politicians will sell out their ideals or break their promises if it will increase their power.” It didn’t measure general wariness. It measured negative beliefs about the establishment.

The common thread between distrust and cynicism, as defined in these experiments, is a perception of bad character. More broadly, it’s a tendency to focus on intention and agency, rather than randomness or causal complexity. In extreme form, it can become paranoia. In mild form, it’s a common weakness known as the fundamental attribution error—ascribing others’ behavior to personality traits and objectives, forgetting the importance of situational factors and chance. Suspicion, imagination, and fantasy are closely related.

The more you see the world this way—full of malice and planning instead of circumstance and coincidence—the more likely you are to accept conspiracy theories of all kinds. Once you buy into the first theory, with its premises of coordination, efficacy, and secrecy, the next seems that much more plausible.

Many studies and surveys have documented this pattern. Several months ago, Public Policy Polling asked 1,200 registered U.S. voters about various popular theories. Fifty-one percent said a larger conspiracy was behind President Kennedy’s assassination; only 25 percent said Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Compared with respondents who said Oswald acted alone, those who believed in a larger conspiracy were more likely to embrace other conspiracy theories tested in the poll. They were twice as likely to say that a UFO had crashed in Roswell, N.M., in 1947 (32 to 16 percent) and that the CIA had deliberately spread crack cocaine in U.S. cities (22 to 9 percent). Conversely, compared with respondents who didn’t believe in the Roswell incident, those who did were far more likely to say that a conspiracy had killed JFK (74 to 41 percent), that the CIA had distributed crack (27 to 10 percent), that the government “knowingly allowed” the 9/11 attacks (23 to 7 percent), and that the government adds fluoride to our water for sinister reasons (23 to 2 percent).

The appeal of these theories—the simplification of complex events to human agency and evil—overrides not just their cumulative implausibility (which, perversely, becomes cumulative plausibility as you buy into the premise) but also, in many cases, their incompatibility. Consider the 2003 survey in which Gallup asked 471 Americans about JFK’s death. Thirty-seven percent said the Mafia was involved, 34 percent said the CIA was involved, 18 percent blamed Vice President Johnson, 15 percent blamed the Soviets, and 15 percent blamed the Cubans. If you’re doing the math, you’ve figured out by now that many respondents named more than one culprit. In fact, 21 percent blamed two conspiring groups or individuals, and 12 percent blamed three. The CIA, the Mafia, the Cubans—somehow, they were all in on the plot.

Two years ago, psychologists at the University of Kent led by Michael Wood (whoblogs at a delightful website on conspiracy psychology), escalated the challenge. They offered U.K. college students five conspiracy theories about Princess Diana: four in which she was deliberately killed, and one in which she faked her death. In a second experiment, they brought up two more theories: that Osama Bin Laden was still alive (contrary to reports of his death in a U.S. raid earlier that year) and that, alternatively, he was already dead before the raid. Sure enough, “The more participants believed that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they believed that she was murdered.” And “the more participants believed that Osama Bin Laden was already dead when U.S. special forces raided his compound in Pakistan, the more they believed he is still alive.”

Another research group, led by Swami, fabricated conspiracy theories about Red Bull, the energy drink, and showed them to 281 Austrian and German adults. One statement said that a 23-year-old man had died of cerebral hemorrhage caused by the product. Another said the drink’s inventor “pays 10 million Euros each year to keep food controllers quiet.” A third claimed, “The extract ‘testiculus taurus’ found in Red Bull has unknown side effects.” Participants were asked to quantify their level of agreement with each theory, ranging from 1 (completely false) to 9 (completely true). The average score across all the theories was 3.5 among men and 3.9 among women. According to the authors, “the strongest predictor of belief in the entirely fictitious conspiracy theory was belief in other real-world conspiracy theories.”

Clearly, susceptibility to conspiracy theories isn’t a matter of objectively evaluating evidence. It’s more about alienation. People who fall for such theories don’t trust the government or the media. They aim their scrutiny at the official narrative, not at the alternative explanations. In this respect, they’re not so different from the rest of us. Psychologists and political scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that “when processing pro and con information on an issue, people actively denigrate the information with which they disagree while accepting compatible information almost at face value.” Scholars call this pervasive tendency “motivated skepticism.”

Top Comment

People cant accept how easily one lone gun man or a few guys with a bomb can totally change people's lives. More...

529 CommentsJoin In

Conspiracy believers are the ultimate motivated skeptics. Their curse is that they apply this selective scrutiny not to the left or right, but to the mainstream. They tell themselves that they’re the ones who see the lies, and the rest of us are sheep. But believing that everybody’s lying is just another kind of gullibility.

http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2015/05/05/conspiracy-theory-as-a-personality-disorder/

[h=1]Conspiracy Theory as a Personality Disorder?[/h] by Kerry R Bolton May 5, 2015 15 Comments

The treatment of "conspiracy theories" by the US intelligentsia is reminiscent of the Soviet commissions that labeled political dissidents mentally ill.

John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at Camp David, April 22, 1961 (John F. Kennedy Library)

John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at Camp David, April 22, 1961 (John F. Kennedy Library)

Download this essay (PDF)

While psychiatry as a means of repressing political dissent was well-known for its use the USSR, this occurred no less and perhaps more so in the West, and particularly in the USA. While the case of Ezra Pound is comparatively well-known now, not so recognized is that during the Kennedy era in particular there were efforts to silence critics through psychiatry. The cases of General Edwin Walker, Fredrick Seelig, and Lucille Miller might come to mind.

As related by Seelig, the treatment meted out to political dissidents in psychiatric wards and institutions could be hellish. Over the past few decades however, such techniques against dissent have become passé, in favor of more subtle methods of social control. While the groundwork was laid during the 1940s by President Franklin Roosevelt calling dissidents to his regime the “lunatic fringe,” this became a theme for the social sciences, the seminal study of which is The Authoritarian Personality by Theodor Adorno et al. This Zionist-funded study established an “F” scale in which respondents were tested for latent “Fascism.” The extent depended on their attitudes towards hitherto what was regarded as traditionally normative values, such as affection for parents and the family, the latter in particular regarded by these social scientists as the seed-bed of “Fascism.”

While social mores have been established to make dissidents pariahs, to impose a soft totalitarianism of the Huxleyan Brave New World variety, social scientists remain occupied with creating new approaches for the continuing de-legitimizing of dissident opinions. Among the primary targets are those who have in recent years been termed “conspiracists.” The term is used to induce a pavlonian reflex in nullifying dissident views on a range of subjects, like the words “racist, “fascist,” “sexist,” etc. Any hint of “conspiracism” in a paper is also sufficient to prevent it from even reaching the initial stage of peer review if submitted to a supposedly academic journal, where one might expect a range of views to be debated.

Recently a group of psychologists studying the allegedly contradictory nature of conspiracy beliefs were able to furnish mind-manipulators with a study that can be used to show that anything associated with or labelled as “conspiracy theory” can be relegated to the realm of mental imbalance. The paper was published as “Dead and Alive: Beliefs in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories.”[1] The abstract reads:

Conspiracy theories can form a monological belief system: A self-sustaining worldview comprised of a network of mutually supportive beliefs. The present research shows that even mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively correlated in endorsement. In Study 1 (n ¼ 137), the more participants believed that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they believed that she was murdered. In Study 2 (n ¼ 102), the more participants believed that Osama Bin Laden was already dead when U.S. special forces raided his compound in Pakistan, the more they believed he is still alive. Hierarchical regression models showed that mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively associated because both are associated with the view that the authorities are engaged in a cover-up (Study 2). The monological nature of conspiracy belief appears to be driven not by conspiracy theories directly supporting one another but by broader beliefs supporting conspiracy theories in general.[2]

The conclusion is that conspiracy theorists have a generalized suspicion of all authority and thereby believe that any event is the product of a conspiracy by authority. Several categories were used to score contradictory attitudes in regard to conspiracy. The subjects were chosen from 137 undergraduate psychology students. Five questions were asked regarding conspiratorial beliefs in Princess Diana’s death.[3] The results “suggest that those who distrust the official story of Diana’s death do not tend to settle on a single conspiracist account as the only acceptable explanation; rather, they simultaneously endorse several contradictory accounts.”[4]

There are several factors to consider:

In is of interest that Wood, Douglas, and Sutton draw on The Authoritarian Personality in creating a psychological profile of conspiracists that will accord with the Liberal-Left assumptions of “conspiracists” as “fascists’ and “anti-Semites”: “There are strong parallels between this conception of a monological belief system and Adorno et al.’s (1950) work on prejudice and authoritarianism.”[5] The purpose of the study can be discerned from this passage:

If Adorno’s explanation for contradictory antisemitic beliefs can indeed be applied to conspiracy theories, conspiracist beliefs might be most accurately viewed as not only monological but also ideological in nature. Just as an orthodox Marxist might interpret major world events as arising inevitably from the forces of history, a conspiracist would see the same events as carefully orchestrated steps in a plot for global domination. Conceptualizing conspiracism as a coherent ideology, rather than as a cluster of beliefs in individual theories, may be a fruitful approach in the future when examining its connection to ideologically relevant variables such as social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism.[6]

Conspiracism is identified as inherently “right-wing authoritarian” ideology. The authors, Wood, Douglas, and Sutton, thereby show themselves to be ideologically biased and agenda-driven; in the same manner as Adorno, et al. Moreover, in ascribing “conspiracism” to “right-wing ideology’” there seems to be a remarkable ignorance as to the diversity of “conspiracists.”

What is one to make, for example, of Carroll Quigley, Professor of History at Harvard and Georgetown University Foreign Service School, whose academic magnum opus Tragedy & Hope, is often quoted by “conspiracists.” This includes several dozen pages describing an “international network” of bankers whose aim is to bring about a centralized world political and financial control system.[7] Despite the relatively few pages on this network in Quigley’s 1,300-page tome, he regarded the role of this network in history, over the course of several generations, as not only pivotal, but also as laudable (apart from its ‘secrecy”).[8]

Wood, Douglas, and Sutton begin their paper with the definition: “A conspiracy theory is defined as a proposed plot by powerful people or organizations working together in secret to accomplish some (usually sinister) goal.”[9] Based on that definition, it would seem difficult to conclude anything other than that Quigley was describing conspiracy, insofar as it is:

What can one make also of the “warning” to the American people by Dwight Eisenhower during his “farewell speech,” in which he referred to the ‘military industrial complex,” which became a favorite expression of the Left? Eisenhower pointed out its wide ramifications, not only economic and political but also on moral and cultural levels. He stated of this:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist….

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded. Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.[11]

Here are the primary elements for “conspiracy theory” in Eisenhower’s address:

For we are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence—on infiltration instead of invasion, on subversion instead of elections, on intimidation instead of free choice, on guerrillas by night instead of armies by day. It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations.[12]

Kennedy used the word “conspiracy.” He was a “conspiracist” in today’s derogative terminology.

Are we really to believe that it is mentality questionable to state that the Bilderbergers for example are a “conspiracy” with a globalist agenda when they have all the facets of a “ conspiracy,” other than to decide subjectively whether such cabals have an evil or a noble intent?

Would Eisenhower score as a “right-wing authoritarian” on Adorno’s personality tests, or as “monological” on the tests of Wood, Douglas, and Sutton? Would Quigley? Kennedy? Would Professor Michel Chossudovsky and the large number of academics who are involved with the Centre for Research on Globalization[13] be characterised as ‘monological” and “right-wing authoritarians’ by Wood, Douglas and Sutton? Perhaps what is required is a screening process whereby “conspiracists” of the “Left” are distinguished from “conspiracists” of the “Right,” allowing the former to retain their legitimacy, while the latter can be subjected to either public anathema or psychiatric treatment, such as lobotomy, medication, or long-term confinement?

Therefore, it seems that there must be arbiters from on high to determine what “conspiracy theories” are socially and politically acceptable and what are not, reminiscent of the Soviet psychiatric commissions that examined political dissidents and diagnosed mental illness.

Dr Karen Douglas describes her academic focus:

My primary research focus is on beliefs in conspiracy theories. Why are conspiracy theories so popular? Who believes them? Why do people believe them? What are some of the consequences of conspiracy theories and can such theories be harmful?[14]

The description implies that “conspiracy theorists” are apt subjects for psychological diagnosis, because they are intrinsically “harmful” to society, like Adorno’s suspicion of the family as the seed-bed of “Fascism.”

References:

[h=1]Conspiracy Theory as a Personality Disorder?[/h] by Kerry R Bolton May 5, 2015 15 Comments

The treatment of "conspiracy theories" by the US intelligentsia is reminiscent of the Soviet commissions that labeled political dissidents mentally ill.

John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at Camp David, April 22, 1961 (John F. Kennedy Library)

John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at Camp David, April 22, 1961 (John F. Kennedy Library)Download this essay (PDF)

While psychiatry as a means of repressing political dissent was well-known for its use the USSR, this occurred no less and perhaps more so in the West, and particularly in the USA. While the case of Ezra Pound is comparatively well-known now, not so recognized is that during the Kennedy era in particular there were efforts to silence critics through psychiatry. The cases of General Edwin Walker, Fredrick Seelig, and Lucille Miller might come to mind.

As related by Seelig, the treatment meted out to political dissidents in psychiatric wards and institutions could be hellish. Over the past few decades however, such techniques against dissent have become passé, in favor of more subtle methods of social control. While the groundwork was laid during the 1940s by President Franklin Roosevelt calling dissidents to his regime the “lunatic fringe,” this became a theme for the social sciences, the seminal study of which is The Authoritarian Personality by Theodor Adorno et al. This Zionist-funded study established an “F” scale in which respondents were tested for latent “Fascism.” The extent depended on their attitudes towards hitherto what was regarded as traditionally normative values, such as affection for parents and the family, the latter in particular regarded by these social scientists as the seed-bed of “Fascism.”

While social mores have been established to make dissidents pariahs, to impose a soft totalitarianism of the Huxleyan Brave New World variety, social scientists remain occupied with creating new approaches for the continuing de-legitimizing of dissident opinions. Among the primary targets are those who have in recent years been termed “conspiracists.” The term is used to induce a pavlonian reflex in nullifying dissident views on a range of subjects, like the words “racist, “fascist,” “sexist,” etc. Any hint of “conspiracism” in a paper is also sufficient to prevent it from even reaching the initial stage of peer review if submitted to a supposedly academic journal, where one might expect a range of views to be debated.

Recently a group of psychologists studying the allegedly contradictory nature of conspiracy beliefs were able to furnish mind-manipulators with a study that can be used to show that anything associated with or labelled as “conspiracy theory” can be relegated to the realm of mental imbalance. The paper was published as “Dead and Alive: Beliefs in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories.”[1] The abstract reads:

Conspiracy theories can form a monological belief system: A self-sustaining worldview comprised of a network of mutually supportive beliefs. The present research shows that even mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively correlated in endorsement. In Study 1 (n ¼ 137), the more participants believed that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they believed that she was murdered. In Study 2 (n ¼ 102), the more participants believed that Osama Bin Laden was already dead when U.S. special forces raided his compound in Pakistan, the more they believed he is still alive. Hierarchical regression models showed that mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively associated because both are associated with the view that the authorities are engaged in a cover-up (Study 2). The monological nature of conspiracy belief appears to be driven not by conspiracy theories directly supporting one another but by broader beliefs supporting conspiracy theories in general.[2]

The conclusion is that conspiracy theorists have a generalized suspicion of all authority and thereby believe that any event is the product of a conspiracy by authority. Several categories were used to score contradictory attitudes in regard to conspiracy. The subjects were chosen from 137 undergraduate psychology students. Five questions were asked regarding conspiratorial beliefs in Princess Diana’s death.[3] The results “suggest that those who distrust the official story of Diana’s death do not tend to settle on a single conspiracist account as the only acceptable explanation; rather, they simultaneously endorse several contradictory accounts.”[4]

There are several factors to consider:

- The small number of subjects drawn from the same background.

- Whether the belief in contradictory theories is rather the willingness to accept several alternatives rather than being bound to a single explanation.

- The tests appear to be of a “tick the boxes” character, and do not appear to offer the subjects opportunity to explain their views.

- The test therefore seems to be nothing other than very limited statistical surveys from which a generalised theory is postulated in regard to “conspiracism.”

In is of interest that Wood, Douglas, and Sutton draw on The Authoritarian Personality in creating a psychological profile of conspiracists that will accord with the Liberal-Left assumptions of “conspiracists” as “fascists’ and “anti-Semites”: “There are strong parallels between this conception of a monological belief system and Adorno et al.’s (1950) work on prejudice and authoritarianism.”[5] The purpose of the study can be discerned from this passage:

If Adorno’s explanation for contradictory antisemitic beliefs can indeed be applied to conspiracy theories, conspiracist beliefs might be most accurately viewed as not only monological but also ideological in nature. Just as an orthodox Marxist might interpret major world events as arising inevitably from the forces of history, a conspiracist would see the same events as carefully orchestrated steps in a plot for global domination. Conceptualizing conspiracism as a coherent ideology, rather than as a cluster of beliefs in individual theories, may be a fruitful approach in the future when examining its connection to ideologically relevant variables such as social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism.[6]

Conspiracism is identified as inherently “right-wing authoritarian” ideology. The authors, Wood, Douglas, and Sutton, thereby show themselves to be ideologically biased and agenda-driven; in the same manner as Adorno, et al. Moreover, in ascribing “conspiracism” to “right-wing ideology’” there seems to be a remarkable ignorance as to the diversity of “conspiracists.”

What is one to make, for example, of Carroll Quigley, Professor of History at Harvard and Georgetown University Foreign Service School, whose academic magnum opus Tragedy & Hope, is often quoted by “conspiracists.” This includes several dozen pages describing an “international network” of bankers whose aim is to bring about a centralized world political and financial control system.[7] Despite the relatively few pages on this network in Quigley’s 1,300-page tome, he regarded the role of this network in history, over the course of several generations, as not only pivotal, but also as laudable (apart from its ‘secrecy”).[8]

Wood, Douglas, and Sutton begin their paper with the definition: “A conspiracy theory is defined as a proposed plot by powerful people or organizations working together in secret to accomplish some (usually sinister) goal.”[9] Based on that definition, it would seem difficult to conclude anything other than that Quigley was describing conspiracy, insofar as it is:

- “Secret,” which Quigley laments as being the primary cause of his disagreement with it,

- Composed of powerful people or organizations,

- Aims to accomplish a specific goal.

What can one make also of the “warning” to the American people by Dwight Eisenhower during his “farewell speech,” in which he referred to the ‘military industrial complex,” which became a favorite expression of the Left? Eisenhower pointed out its wide ramifications, not only economic and political but also on moral and cultural levels. He stated of this:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist….

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded. Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.[11]

Here are the primary elements for “conspiracy theory” in Eisenhower’s address:

- There is a threat that is obviously “secret,” or at least not above-board, otherwise Eisenhower would not see the need to make it a feature of his final words as President.

- This threat involves a cabal: “the military industrial complex,” and a technocratic “elite.”

- The threat involves “the power of money.”

- The threat is that of the accumulation of power by these elites.